I started to write this as a typical blog post, with fairly informal language and aimed at discussions I have been following on the internet. But the article ballooned in length and, as a result, I have come to see this as more like a first-draft of a scholarly article. So, I edited the language and approach to references to be a bit more scholarly. I’d really appreciate feedback. (Word count: 6420) Thanks!

[IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: I am an OER Coordinator at Houston Community College. In that capacity, I advocate for the adoption of OER and I work closely with several OER courseware platform providers. This article is my attempt to think through issues that I confront in practice. But I try to do so from as objective and theoretical a standpoint as I can.]

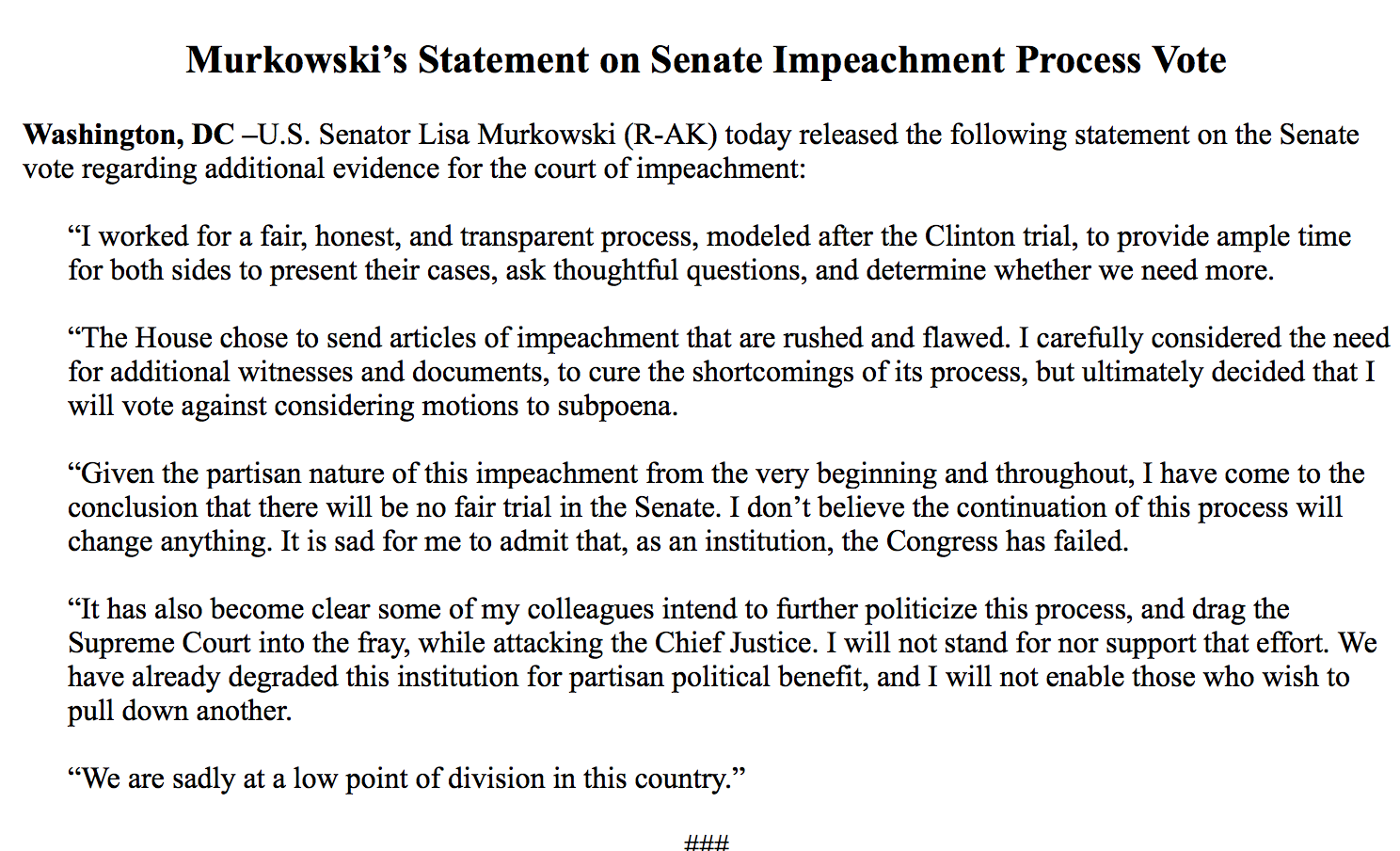

As Open Educational Resources (OER) mature, they face many of the same questions that have faced other learning technologies and learning platforms. Given a larger and better-produced catalogue of OER, a large segment of for-profit companies have pursued a marketing and development strategy known as “open wrapping.”[i] The growth of courseware and technology platforms to support OER and the blend of for-profit with non-profit support for OER will present pressing issues for the near future open education. Questions about the benefits and harms of courseware and technology platforms apply to all aspects of education, but in the “open” space, those questions take on a specific character. First, for many people, the value of OER comes from their promise to reform a broken textbook market, providing materials that have a perpetual, open license. Second, open education advocates emphasize normative reasons for adopting, using, and developing OER, including not only social justice concerns about reducing barriers of access to education, but also intellectual property concerns about democratizing and publicizing a shared knowledge base for the modern world. These normative and economic concerns that guide OER usage highlight the special challenges of courseware platforms, but the ethical issues raised can be easily generalized to apply to any use of software platforms in education.

In order to address those concerns, I will begin by outlining a framework for evaluating the ethical issues posed by open wrapping. That framework consists of two parts: an outcomes-oriented evaluation and an evaluation of appropriate constraints based on considerations for the rights of users. In the outcomes-oriented evaluation, I will assess two different areas of possible benefit and harm posed by the adoption of OER courseware: first, benefits and harms to the sustainability of the OER ecosystem and second benefits and harms to teaching and learning through the implementation of OER courseware. In the section on constraints, I outline the mechanisms by which courseware platforms are designed to harvest user data in ways that do not always respect the labor, autonomy, or consent of users. Consequently, data monetization presents potential rights violations for users. Particularly in education, where students are required to use a platform because it is assigned by an instructor, those potential rights violations are ethically serious. Finally, I turn to some broader, systemic concerns that do not fall neatly into either outcomes or constraints considerations. These systemic concerns suggest the need to be vigilant about the ways that digital courseware is continuing to define and restrict education.

Open wrapping is a growing segment of OER and courseware is a growing segment of the overall educational technology market. While the issues presented by open wrapping emerge in considerations of OER particularly because of the normative concerns that drive many to adopt OER, those same considerations apply more generally to any use of courseware platforms in education. In the end, I provide a framework for instructors to evaluate software platforms that they adopt and use, but I arrive at the conclusion that the use of courseware is a pedagogical decision. Each instructor should weigh the benefits and harms and make a judgment based on their pedagogical preferences.

A Basic Moral Framework

One attractive and relatively clear way to assess the ethical implications of a moral decision is to weigh the likely outcomes. One might list the relevant goods or harms that may be produced by a given course of action, then assess the probable quantity of goods as compared to the probable quantity of harms. This is intuitively objective way to inform moral judgments. It can be quite a bit more sophisticated than the classical utilitarian calculus with which many people are familiar. For one thing, we may recognize a list of goods or harms much broader than simply pleasure or pain. For another, we needn’t restrict the comparison to a purely quantifiable calculus. We may recognize that the goods or harms are not strictly quantifiable, but we can still enumerate them in a way to facilitate judgment. I will call this approach the “outcomes-oriented assessment.”

There will always be problems with an outcomes-oriented assessment because our knowledge of future outcomes is limited and we may miscalculate. But even when a certain course of action presents very clear benefits, outweighing potential harms, there still may be reasons to reject that course of action because it transgresses some moral obligation that we take to be fundamental. To make this idea more concrete, I will assume that most human persons have something like rights, that is, certain fundamental freedoms that cannot be infringed. Rights-talk is pretty intuitive and fairly pervasive in political conversations even though philosophers have been critical of it.[ii] I set those concerns aside for the present argument. For the purposes of this discussion, if a person has a right to something, then that right entails that others must refrain from infringing on that right. If Nancy has an unqualified right to speech, then no one else can be permitted to curtail Nancy’s speech. In other words, Nancy’s right places a corresponding obligation on everyone else. Everyone else is constrained in their actions by Nancy’s right to speak. Thus, the existence of rights places constraints on actions that might violate those rights.

Consequently, my moral framework for assessing the benefits and harms of or OER courseware will first assess the outcomes of adopting such courseware, but then it will also consider the moral constraints that ought to operate on our calculus. If any of those outcomes might result in infringing on the rights of others, then we have to constrain our actions, out of respect for those rights, no matter how beneficial the outcomes may be. On this view, constraints trump outcomes. One cannot accept even the most beneficial outcomes if they run roughshod over rights.[iii]

The Benefits and Harms of OER Courseware: An Outcomes-Oriented Assessment

To assess the possible benefits and harms of courseware, one should appreciate that courseware platforms blend different types of things. Courseware combines instructional content into a software platform that is then fed into a Learning Management System (LMS). Decisions about how the courseware is constructed are the result of different instructional design objectives. Assessing the value of courseware for OER courses involves an assessment of the content, the platform, the instructional design, and its interoperability with other platforms (like the LMS). In typical OER courseware options, content is openly licensed (though some quiz or test banks may be proprietary or may have a different license type from the rest of the content). The content may be pulled from existing OER or it may be developed by the courseware provider. This could be true for “ancillary” resources, like assessments and activities embedded into the courseware, or it may be that the core instructional content, the “textbook,” is developed by the courseware provider.

Broad Outcomes of OER Courseware

It bears stating that the primary outcome that should concern an evaluation of OER courseware is whether the courseware actually helps students learn the material. That said, it may be useful to consider broader implications of courseware providers for the OER ecosystem. OER courseware companies have infused resources into developing OER content and modifying OER to embed that content into courseware platforms. Though the trajectory of those investments remains unclear, it is possible that OER courseware will continue to be seen as a profitable growth sector of the textbook industry. It’s also possible that investment in OER represents a momentary bubble in the market. In either case, current investment in the OER courseware market has presented opportunities for raising the quality, quantity, and accessibility of OER for instruction. One ideal scenario may see open wrapping as a component in the long-term sustainability of OER. But, even if that is not the case, as long as the content created through open wrapping ventures is openly licensed, open wrapping courseware will have generated a greater quantity of usable OER content. There are concerns that some OER courseware platforms do not enable sharing and repurposing of OER content in a way that aligns with the spirit of the open license.[iv] These concerns may mitigate enthusiasm about the creation of open content in an open wrapping arrangement.

Are there broader harms that may be caused by open wrapping? Perhaps one could argue that OER courseware crowds out investment in more public forms of OER infrastructure. As schools invest in partnerships with for-profit OER providers, they have less money to invest in their own OER development. To understand the trade-off, consider a dollar spent on a for-profit OER courseware provider versus the same dollar spent by a college on internal infrastructure and OER development. Which dollar is spent more efficiently? Perhaps internal spending is more efficient because it makes use of existing resources at the college whereas external spending supports the creation of an independent infrastructure. Conversely, independent companies that build courseware infrastructure can gain efficiency by sharing content with many different educational institutions and repackaging that content for use in different contexts. To assess the relative efficiency of each model, we might consider the prevalence of for-profit academic presses versus university presses. While the academic publishing market contains a large portion of not-for-profit presses, university presses compose a much smaller fraction of total journals and publishers.[v] It’s not necessary to assume a perfectly free market of academic publishing to concede that for-profit publishing seems to work as a financial proposition. If the courseware market is analogous to the academic publishing market, it seems unlikely that economic efficiency alone could rule out the benefit of for-profit OER courseware platforms.

Even if the economics point to a benefit from the use of for-profit publishers, there might be mission preferences that counsel against it. Perhaps dollars should be spent in ways that prioritize public institutions of higher education before private courseware companies because there is some intrinsic value to the promotion of public educational institutions. If that is conceded, then there may be some reasons to prefer spending dollars on the less efficient but more intrinsically valuable non-profit infrastructure. Nevertheless, it would be irrational to insist on higher education’s obligation to support projects that have intrinsic value in the face of economic insolvency.[vi] So, the degree to which this line of thought would weigh heavily against for-profit companies producing and supporting OER will have to be constrained, at least in part, by the economics.

When considering the economic impacts of OER courseware, it’s important not to forget the economic impacts of such courseware on students. While OER courseware platforms are typically much less expensive than platforms support traditional, commercial textbooks, they usually introduce some cost to students. Those costs may pose barriers to access. Whenever educators introduce such barriers, they risk alienating some students – typically, the students who need access to education most. The practice of introducing cost barriers that keep students out of educational opportunities can be understood under the rubric of “digital redlining.”[vii] Such practices can have the effect of increasing existing social inequalities. I will discuss these issues further in the final section on systemic concerns.

Outcomes Related Directly to Teaching and Learning

So much for the broader impacts. The primary focus on outcomes should be on teaching and learning. On this count, there is an argument to be made that courseware platforms, for OER or otherwise, provide value to teaching and learning. The science of teaching seems to have arrived at a few components of instructional design that measurably improve recall, learning, and mastery of content. First, there appears to be robust evidence that actively engaging students in required practice in low-to-moderate stakes environments improves learning. This has been demonstrated with studies measuring the testing effect,[viii] the doer effect,[ix] and effortful retrieval.[x] When students are required to generate responses in a way that challenges them, even if they feel like they are struggling, their gains in learning are markedly better. I say that the findings are robust because there appear to be many different experimental designs and contexts that demonstrate a similar effect. Given these findings, it is fair to conclude that students will remember more content and master more challenging concepts if they are required to engage in assignments where they are tested on their knowledge and generate responses by retrieving content from prior learning.

Along similar lines, studies have shown that interleaved practice and spacing between practice helps learning. The classic model for college classes assigns one or two big tests or papers (a mid-term and final) which encourages students to try to cram information through mass studying sessions. But this practice is counterproductive to long-term retention. Instead, studies show that students are best served by regular studying over shorter periods. Additionally, students ought to regularly return to earlier concepts throughout the course rather than studying concepts purely sequentially (this the idea behind interleaved testing). Just because a chapter is finished doesn’t mean the concepts ought to be forgotten. Long-term memory is improved by requiring students to retrieve material they have already learned in previous sections of the course.

How do these results from the science of teaching and learning relate to courseware? Many courseware platforms are designed with these principles in mind. Not all of them, of course. And when evaluating a software platform, instructors should look for platforms that provide active learning measures, regular testing, interleaved practice, and spaced studying. But if a platform does provide these or similar features, then there is good reason to believe that adopting a platform will actually improve student learning.

One may object that a software platform is not necessary to achieve these results. After all, any well-designed course can implement these learning techniques. While technically true, I think it is practically false. We need to be realistic about the time commitment, technical requirements, and knowledge of instructional design that are required in order to effectively design a course that employs all of these techniques.[xi] Instructors may legitimately feel that they cannot reproduce the quality of courseware design provided by for-profit courseware providers on their own.

So, those are the benefits to teaching and learning from adopting courseware, but what are the harms? One line of argument against courseware platforms can be classed under the broad heading of “critical digital pedagogy.” This view emphasizes the autonomy of learners as the primary goal of education, particularly in an age when educational relationships are mediated by digital technologies. The idea is that once a course has built in all of the capabilities I identify above – regular, interleaved assessment, required spacing in studying – and others that I didn’t – like learning pathways or adaptive learning exercises – these platforms put a straight-jacket on the learning process, infantilize learners, and cut short the dialogic model of education, where teacher and learner are engaged in a cooperative process of discovery. In effect, the critique says that by building such robust support-structures around the learning experience, we deprive the learning experience of its vitality and reduce the autonomy of learners, similar to the way putting your limbs in a cast will cause your muscles to atrophy.

It strikes me that, in the end, this boils down to a difference of pedagogical theory. Some instructors prefer their classrooms to mimic a democratic and fluid conversation, where teachers and learners both contribute to an active, open environment. Other instructors prefer a more predictable, sequenced learning experience that delivers consistent results. For those who prefer the former, OER courseware may not make sense, but those who prefer the latter may prefer it. It may be tempting to think that this difference in approach aligns with disciplinary differences. The humanities and social sciences may be more inclined toward critical pedagogy, while the more quantitative and technical fields will require a more structured environment. This may have a ring of truth, but there will be exceptions on the margins. The important thing to recognize is that the value of courseware for teaching and learning is one that is probably best assessed by the educator according to their educational goals and style.[xii]

Side Constraints and the Use of OER Courseware

Granted the outcomes-oriented assessment of OER courseware, some objections to for-profit courseware platforms suggest that such platforms may violate students’ rights in ways that cannot be tolerated. The language of rights introduces what Robert Nozick has called “side constraints.”[xiii] If OER courseware is engaged in rights violations, then there ought to be side constraints placed on instructional practice such that the use of such courseware is constrained in ways to avoid rights violations.

In what ways might OER courseware violate rights? Primarily, concerns about rights violations come from data monetization. Educational technology companies, like all technology companies today, include within their business model the use of user data for marketing, product design, and trouble-shooting. Some of these are desirable. For example, if data on student responses help designers to improve or correct quiz questions or improve instructional design, this seems desirable.[xiv] If features in the platform are unused or misused because they don’t work properly or are poorly designed, then data can help fix it. In general, when data is used to improve the educational experience of students, this seems like an appropriate use of the data. And if a company can monetize that experience by selling a better product, then so much the better for students.

The problem is that it is impossible to know whether technology companies are using student data for these beneficial purposes or whether they are using them for other purposes that students would not consent to if they were understood. For instance, the platform may have an interest in keeping students engaged for longer periods of time even if they aren’t learning. More insidiously, companies may use user data to market to students outside of the platform. After all, most students create user accounts with an email address. Additionally, they may answer questions or take certain courses that provide the courseware company with information about their interests and that information might be useful for marketing purposes. Most basically, courseware platforms asses student learning, which may provide insight into student interests, the way they process information, or other behavioral patterns. All of this information could be useful to advertisers, employers, and others. [xv] If courseware platforms monetize student data by producing products outside the platform and beyond the educational experience, that may be a use that students would not consent to, had they known in advance.

Perhaps the clearest case of ethically problematic data usage comes from platforms for which student work is essential to the business model, namely, Plagiarism Detection Software (PDS). For instance, Turnitin uses its huge database of student papers to perform plagiarism checks on other student submissions. In the case of Turnitin, a student pays for access to the platform (either by directly purchasing an access code, through a student technology fee, or through tuition) and then their work on the platform is used by the platform in order for it to function. Jesse Stommel and Sean Morris call this an “abuse of student labor and intellectual property.”[xvi] As cited in that article, the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s committee on intellectual property concurs that PDSs “can violate students’ right to privacy by making student writing available to commercial third parties not engaged in the relationship implied in the educational process.”[xvii] At least in the case of PDS, it appears that some educators assert that online courseware platforms violate the rights of students.

The argument appears to be

- Students have a right not to have their intellectual property (or personal data) used by commercial third parties in ways that they do not consent to.

- Students do not consent to having their intellectual property (or personal data) used in the ways Turnitin or other PDS platforms do.

- Therefore, Turnitin and other PDS platforms violate the rights of students.

The argument is pretty clearly valid. The first premise seems plausible given that it is a truism for anyone else. One may argue, against the second premise, that students consent to certain uses of their intellectual property and personal data for the purposes of education when they enroll in an educational institution. For instance, students submit their work to teachers for grading without being compensated monetarily. Similarly, various departments in the college use student data to inform decisions around completion, advising, etc. But the reply is clear: whereas student data may be used in explicitly educational functions, Turnitin and other companies use these data in ways that are not directly connected to the student’s own education. For instance, a student’s paper at one college may be used to detect plagiarism for another student at a different college. This function extends beyond the educational arrangement that a student consented to when they enrolled in the college or course.

Nevertheless, one may press on, students consent to this arrangement when they agree to Turnitin’s terms of service. But Stommel and Morris find that the explicit marketing claims made by Turnitin contradict the details of their terms of service. Turnitin’s claims on its website it “does not ever assert or claim copyright ownership of any works submitted to or through our service. Your property is YOUR property.” Yet, when Stommel and Morris analyze the terms of service, they conclude, “The gist: when you upload work to Turnitin, your property is, in no reasonable sense, YOUR property.”[xviii] While the public statements may be true by way of legal technicality, they are misleading. Such misleading statements vitiate the consent students provide when they accept the terms of service. Would students agree to participate with Turnitin if they were told, explicitly, in plain English, how the business works? More to the point, if a student refuses to accept the terms of service, would their professors allow them to opt-out of this portion of the class? The fact that Turnitin (and other PDS software) are required by professors further undermines the degree to which this arrangement is truly voluntary. So, premise two appears to be accurate in at least some cases. As long as professors require the use of PDS in their classes (over the objections of students on privacy and intellectual property grounds) and as long as those PDS companies misrepresent the way they use student work, then these software programs fail to obtain consent from those students and if the students would not consent to this arrangement, given full knowledge, then use of their data may violate their rights.

How relevant is the case of PDS to other instructional platforms, particularly, OER courseware? At this point, it is fair to assume that all courseware platforms monetize or seek to monetize student data.[xix] Recently, a market research firm, ListEd Tech, published a list of EdTech companies with the data on the most students. Companies are ranked by number of students and differentiated by Higher Ed and School Districts. Google and Microsoft dominate the list, primarily because of their email services, but also from their productivity software.[xx] Audrey Waters notes while many school districts use Google applications because they are free, in reality, “[s]chools pay with their students’ data. (Google might not sell advertising against student data, but it does still utilize this information to fuel its product development and its algorithms.)”[xxi] There are other, more exotic, ways that faculty have enlisted their students in data collection practices without consent. Chris Gilliard provides a few anecdotes in a recent The Chronicle of Higher Education piece. He recognizes that issues surrounding student labor and consent are at the heart of the moral problems posed by educational technology. He concludes, “When we draft students into education technologies and enlist their labor without their consent or even their ability to choose, we enact a pedagogy of extraction and exploitation.”[xxii]

According to the arguments above, use of student data constitutes a rights violation only if the student does not consent to that use. We typically think that adults can consent to relationships that others might find ill-advised and, except in extreme circumstance, only the individual’s personal judgment should constrain those arrangements. This suggests that for most college students, the choice about whether or not they share their intellectual property and personal data with courseware providers should be up to the student. For minors, protections on student data should be more stringent because we cannot suppose that they are in a position to consent to ill-advised use of their data. Gilliard and Sommel and Morris add concerns around fair compensation for student labor, when student work is used to prop up a for-profit enterprise. The enterprise of teaching and learning presupposes that students will work in order to learn, by completing assignments, drafting documents, creating presentations, designing projects, etc. A rights violation only arises when that labor is used by a third-party for a purpose that is not directly connected to the traditional relationship of teaching and learning.

Consequently, we are in a position to offer a test of whether some piece of educational technology violates student rights.

- Does the student consent to the use of her data in the way it is used by the technology?

- Are the products of the student’s labor used only within the traditional arrangement of teaching and learning? That is, is the student’s labor used for the purpose of that student’s learning, assessment, feedback, reward, etc., as is required by the teaching and learning relationship?

While this two-part test may simplify an instructor’s assessment of whether or not they ought to be constrained in their use of courseware platforms, each prong of the test is complex. Consent requires more than just an acceptance of Terms of Service. It ought to be informed consent, meaning that students should understand how their data is being used in words they can understand.[xxiii] Similarly, the “traditional arrangement of teaching and learning” is necessarily vague. Conceivably, every classroom may involve a unique arrangement between instructor and student. So, assessing whether or not student labor is used for purposes outside of that traditional arrangement will require some judgment that cannot be fully prescribed in advance. Nevertheless, this test provides a framework for evaluating whether a courseware should be avoided due to moral side constraints.

Systemic Concerns Around the Use of Courseware in Education

We are not out of the woods yet. There remain concerns about courseware platforms in education that do not fit neatly into either the assessment of outcomes or the evaluation of side constraints. Authors critical of educational technology and courseware platforms also articulate concerns that are more systemic in nature. These systemic concerns are consequences of the use of technology platforms in education, but they are indirect and not easily measured. Similarly, while they present real concerns about the ways educational technology alters the relationship between teachers and students, they do not rise to the level of side constraints. Nonetheless, they are important concerns that ought to be addressed before an evaluation of the ethics of open courseware is complete.

When Gilliard talks about technology and privacy, he sometimes uses the language of rights violations, for instance when he evokes the sense of a violation of privacy and consent.[xxiv] But he also raises structural concerns under the concept of “digital redlining.” The notion of digital redlining, Gilliard says, intentionally refers back to the historical process of racial segregation by those who enforced “grey” norms around housing opportunities, mortgage lending, and rental eligibility. “[Digital redlining] is the creation and maintenance of technological policies, practices, pedagogy, and investment decisions that enforce class boundaries and discriminate against specific groups. The digital divide is a noun; it is the consequence of many forces. In contrast, digital redlining is a verb, the ‘doing’ of difference, a ‘doing’ whose consequences reinforce existing class structures.”[xxv] Digital redlining, like its non-digital, historical predecessor, limits opportunities, restricts access, and impinges on the freedoms of specific populations, not through direct rights violations, but through an indirect set of practices and norms that may even (in some cases) be well-meaning. The problem is that, in their totality, these practices exclude some groups from access to information, freedoms, and a sense of personal agency that others have by default.

Similarly, even though Stommel and Morris demonstrate specific ways that Turnitin (and other PDS) may violate individual rights of students, the broader message of their recent work is to demonstrate how the use of platforms and educational technology truncates the educational experience and limits the possibilities of student agency for personal development. For instance, in “Learning is Not a Mechanism,” Stommel argues that the LMS attempts to automate and make objective a process, particularly the grading and evaluation of student work, that is fundamentally subjective and personal. He worries that as we abstract the essence of student work into tasks that can be automatically graded, we reduce the learning process to its least interesting, most oppressive aspects. It turns learning into machine-like work, removing the relational and transformational aspects of learning. Similarly, Morris, in “Beyond the LMS,” finds that the LMS plays “to the lowest common denominator.” The LMS does not assist instructors in classroom innovation, but encodes the most repetitious and least innovative practices of the classroom into a pervasive digital tool. These arguments do not demonstrate that courseware involves rights violations, nor do they point to specific, negative consequences of adopting courseware. Rather, they recognize that the pervasiveness of courseware and LMS platforms signals a shift away from pedagogy that is engaging and transformative, toward a pedagogy that is rote and mechanical. Stommel and Morris assert that “educators should never be in the business of removing student agency,” but courseware platforms, they argue, do just that.

Likewise, Watters characterizes the move toward “personalized” and adaptive platforms as a reductive move that mechanizes instruction, trades on a consumer-producer model of education, and restricts genuine autonomy. She likens personalized courseware to the famous “Skinner box.” In a Skinner box, the lab rat or pigeon is given options and engages in “choices” that are “conditioned” by the experimenter. But the entire arrangement is deeply unnatural. It results in a feedback mechanism at the lowest level of behavior: action – reward – action – reward. Here, she recognizes that language around pedagogy has shifted from “individualization,” a word with deep resonance with autonomy and freedom, to “personalization,” which is grounded in selecting a set of preferences from among pre-determined options. It’s the logic of consumerism and behaviorism, not the logic of autonomy, growth, or personal development. “’Personalization’,” she writes, “acts as some sort of psychological balm, perhaps, to standardization. A salve. Not a solution.”[xxvi]

These arguments point to a systemic drift in education. As Watters, Stommel, Morris, and Gilliard would readily admit that drift is not new to digital courseware platforms. Rather, these platforms provide a new iteration of a decades-long tension in education. Whereas genuine learning occurs when students are changed, acquiring knew knowledge, habits, skills, or dispositions, some educators appear to want learning to fit a mechanized model of measurement, automation, efficiency, and standardization. This tension is nothing new. But, they would insist, that doesn’t make the need to address it any less pressing.

Conclusion

The challenges presented by possible rights violations and systemic shifts in pedagogy from the widespread adoption of courseware are concerning. They ought to be especially concerning for advocates of OER who premise their advocacy on the reduction of barriers to access and the promotion of social justice. To avoid potential rights violations, instructors need to be up-front about how courseware platforms, required for use in their courses, may use student data. Additionally, they must allow students an opportunity to opt-out of that arrangement on privacy grounds. Otherwise, they risk requiring students to enter a non-consensual arrangement where their personal data and intellectual property may be used by others. In most cases, communication and consent around courseware will be easy for instructors to obtain. Once this bar has been met, then it is up to the instructor to evaluate the direct and indirect pedagogical effects of adopting OER courseware. Instructors should be thoughtful and serious as they reflect on their use of OER courseware and its implications for teaching and learning. Similarly, OER advocates and administrators of OER programs ought to be forthright about objections to OER courseware at the same time as they may advocate for the use of courseware in an effort to increase OER adoptions.

[i] For some helpful context, see J. Young and S. Johson’s interview, “As OER Grows Up, Advocates Stress More Than Just Low Cost,” https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-01-15-as-oer-grows-up-advocates-stress-more-than-just-low-cost; David Wiley, “How do we talk about ‘open’ in the context of courseware?” https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/5440; and Michael Feldstein, “MOOCs, Courseware, and the Course as an Artificat,” https://mfeldstein.com/moocs-courseware-and-the-course-as-an-artifact/.

[ii] See, for instance, Glendon, M., Rights Talk: The Impverishment of Political Discourse (New York: Free Press, 1991).

[iii] This is the basic insight of anti-utilitarian fantasies, like Ursula Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.”

[iv] While there is no evidence that OER courseware providers violate the terms of open copyright licensing by embedding or developing OER content in a platform that makes reuse and repurposing difficult, there is nonetheless a serious concern about the degree to which this platform is genuinely open.

[v] STM Report, Fifth Edition (2018), pg. 40-47. Of the 657 publishers and 11,500 journals, about 73% of those publishers are not-for-profit, producing only 20% of the journals. Oxford and Cambridge University presses stand out as giants among university presses, rivaling the second tier of publishers. But the total share of journals published by university presses is not much more than 10%.

[vi] Consider the case of the recent decision to discontinue Stanford University Press. The press cost the college an average of $16 M a year. It could be argued that the value of such a press, in the context of Stanford’s annual budget (…) and endowment (…) would warrant continuation of the press, but even the most ardent promoter of university presses would have to concede that a university should not be required to countenance mounting annual losses to support an academic press.

[vii] “Digital redlining is the modern equivalent of this historical form of societal division; it is the creation and maintenance of technological policies, practices, pedagogy, and investment decisions that enforce class boundaries and discriminate against specific groups. The digital divide is a noun; it is the consequence of many forces. In contrast, digital redlining is a verb, the “doing” of difference, a “doing” whose consequences reinforce existing class structures.” https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/7/pedagogy-and-the-logic-of-platforms

[viii] See P. Brown, H. L. Roediger II, and M. A. McDaniel, Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Harvard University Press, 2014); K.-H. Bäuml, “Cognitive Psychology of Memor” in Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference (2008); J. D. Karpicke, et al, “Retrieval-Based Learning,” in Psychology of Learning and Motivation (2014); H. L. Roediger III, et al, “Ten Benefits of Testing and Their Applications to Educational Practice,” in Psychology of Learning and Motivation (2011); N. Kornell and K. E. Vaughn, “How Retrieval Attempts Affect Learning,” in Psychology of Learning and Motivation (2016).

[ix] K. R. Koedinger, et al, “Is the Doer Effect a Causal Relationship? How can We Tell and Why It’s Important,” Learning Analytics and Knowledge ’16, 388-397 (2016).

[x] M. A. Pyc and K. A. Rawson, “Testing the retrieval effort hypothesis: Does greater difficulty correctly recalling information lead to higher levels of memory?”, Journal of Memory and Language, 60 (4), 2009, 437-47.

[xi] While I am sympathetic the criticism that instructors who are reliant on courseware platforms have “outsourced” their instructional obligations, I am also sympathetic to instructors who insist that it would be prohibitively time-consuming to design a course that actively engaged students in ways that mimicked what courseware providers can do. I teach philosophy, and apart from a couple of logic courses, I’ve never been impressed by what courseware platforms offer philosophy instructors. As a result, I have always built my classes from the ground up. But I also recognize that my classes fall woefully short of what I’ve seen courseware platforms do in other subjects. I devote a lot of time to designing active learning tasks and quiz banks, but I struggle to build in the kind of functionality that interleaves test questions or requires students to engaged in spaced studying. Sometimes this is because I just haven’t found the functionality in the LMS and sometimes it’s because I haven’t built enough content, can’t find the content, or don’t know how to utilize existing tools to suit my needs.

[xii] At my institution, about a third of our OER courses use some courseware (paid for by an external grant). This means that two-thirds prefer not to use any courseware, even when it’s free to use.

[xiii] Anarchy, State, and Utopia (New York: Basic Books, 1974).

[xiv] See, for instance, R. Bodily, R. Nyland, and D. Wiley, “The RISE Framework: Using Learning Analytics to Automatically Identify Open Educational Resources for Continuous Improvement,” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(2), https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i2.2952

[xv] In 2014, Politico published an article warning about the possible dangers of Knewton/Alta’s data on student learning. The chief concern was that Knewton has a particularly sensitive kind of data, namely, data about how individuals learn, how they persevere on task, and what they know. However, it’s not clear whether these data can be linked to the identity of the learner and whether or how the data is used. For instance, whether it exploits students. https://www.politico.com/story/2014/05/data-mining-your-children-106676

[xvi] “A Guide to Resisting Ed Tech,” An Urgency of Teachers.

[xvii] http://culturecat.net/files/CCCC-IPpositionstatementDraft.pdf

[xviii] “A Guide to Resisting Ed Tech,” An Urgency of Teachers.

[xix] Many people were surprised to learn that Instructure had announced plans to monetize student data, but this represents the trend, not the outlier: https://mfeldstein.com/instructure-plans-to-expand-beyond-canvas-lms-into-machine-learning-and-ai/

[xx] https://www.listedtech.com/blog/edtech-companies-with-the-most-student-data

[xxi] http://2017trends.hackeducation.com/platforms.html

[xxii] https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-Ed-Tech-Is-Exploiting/243020

[xxiii] These considerations appear to align with the suggestions made by Amy Collier regarding the use of student data (“Digital Sanctuary,” New Horizons). She outlines several criteria that ought to be met when considering the use of student data for educational purposes:

- Audit policies associated with the use of student data with third-party providers,

- Have a standard and well-known policy about how to handle requests for student data from third parties,

- Provide data audits to students who request them,

- Take seriously the data policies of third-party vendors, specifically, don’t work with vendors whose contracts stipulate that they can use and share student data without consent,

- Reconsider and evaluate internal tracking protocols on student data, specifically asking whether they truly serve students, and

- Give students technological agency in their interactions with the institution.

[xxiv] See Gilliard, “Privacy is not an abstraction,” https://www.fastcompany.com/90323529/privacy-is-not-an-abstraction

[xxv] “Pedagogy and the Logic of Platforms,” https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/7/pedagogy-and-the-logic-of-platforms. See also Gilliard and Culik, “Digital Redlining, Access, and Privacy,” https://www.commonsense.org/education/articles/digital-redlining-access-and-privacy

[xxvi] Watters, “Teaching Machines, or How the Automation of Education Became ‘Personalized Learning’,” http://hackeducation.com/2018/04/26/cuny-gc